Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (English): Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

<p style="text-align: center;">''Preface''</p> | <p style="text-align: center;">''Preface''</p> | ||

This book will perhaps only be understood by those who have | This book will perhaps only be understood by those who have themselves already thought the thoughts which are expressed in it—or similar thoughts. It is therefore not a text-book. Its object would be attained if there were one person who read it with understanding and to whom it afforded pleasure. | ||

The book deals with the problems of philosophy and shows, as I believe, that the method of formulating these problems rests on the | The book deals with the problems of philosophy and shows, as I believe, that the method of formulating these problems rests on the misunderstanding of the logic of our language. Its whole meaning could be summed up somewhat as follows: What can be said at all can be said clearly; and whereof one cannot speak thereof one must be silent. | ||

The book will, therefore, draw a limit to thinking, or rather—not to thinking, but to the expression of thoughts; for, in order to draw a limit to thinking we should have to be able to think both sides of this limit (we should therefore have to be able to think what cannot be thought). | The book will, therefore, draw a limit to thinking, or rather—not to thinking, but to the expression of thoughts; for, in order to draw a limit to thinking we should have to be able to think both sides of this limit (we should therefore have to be able to think what cannot be thought). | ||

| Line 812: | Line 812: | ||

Absence of this mark means disagreement. | Absence of this mark means disagreement. | ||

4.431 The expression of the agreement and disagreement with the truth-possibilities of the elementary-propositions expresses the truth-conditions of the proposition. The proposition is the expression of its truth- conditions. | 4.431 The expression of the agreement and disagreement with the truth-possibilities of the elementary-propositions expresses the truth-conditions of the proposition. The proposition is the expression of its truth-conditions. | ||

(Frege has therefore quite rightly put them at the beginning, as explaining the signs of his logical symbolism. Only Frege's explanation of the truth-concept is false: if "the true" and "the false" were real objects and the arguments in ~''p'' etc., then the sense of ~''p'' would by no means be determined by Frege's determination.) | (Frege has therefore quite rightly put them at the beginning, as explaining the signs of his logical symbolism. Only Frege's explanation of the truth-concept is false: if "the true" and "the false" were real objects and the arguments in ~''p'' etc., then the sense of ~''p'' would by no means be determined by Frege's determination.) | ||

| Line 935: | Line 935: | ||

5.1 The truth-functions can be ordered in series. That is the foundation of the theory of probability. | 5.1 The truth-functions can be ordered in series. That is the foundation of the theory of probability. | ||

5.101 The truth-functions of every number of | 5.101 The truth-functions of every number of elementary propositions can be written in a schema of the following kind: | ||

{| style="margin: 0 auto 0 auto;" | {| style="margin: 0 auto 0 auto;" | ||

| Line 1,004: | Line 1,004: | ||

5.11 If the truth-grounds which are common to a number of propositions are all also truth-grounds of some one proposition, we say that the truth of this proposition follows from the truth of those propositions. | 5.11 If the truth-grounds which are common to a number of propositions are all also truth-grounds of some one proposition, we say that the truth of this proposition follows from the truth of those propositions. | ||

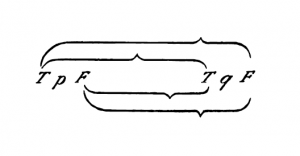

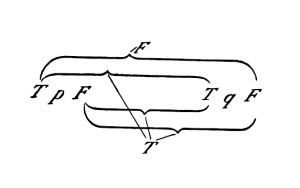

5.12 In particular the truth of a proposition ''p'' follows from that of a proposition ''q'', if all the truth- grounds of the second are truth-grounds of the first. | 5.12 In particular the truth of a proposition ''p'' follows from that of a proposition ''q'', if all the truth-grounds of the second are truth-grounds of the first. | ||

5.121 The truth-grounds of ''q'' are contained in those of ''p''; ''p'' follows from ''q''. | 5.121 The truth-grounds of ''q'' are contained in those of ''p''; ''p'' follows from ''q''. | ||

| Line 1,066: | Line 1,066: | ||

Contradiction is the external limit of the propositions, tautology their substanceless centre. | Contradiction is the external limit of the propositions, tautology their substanceless centre. | ||

5.15 If ''T<sub>r</sub>'' is the number of the truth-grounds of the proposition "''r''", ''T<sub>r</sub>'' the number of those truth-grounds of the proposition "''s''" which are at the same time truth-grounds of "''r''", then we call the ratio ''T<sub>rs</sub>:T<sub>r</sub>'' the measure of the ''probability'' which the proposition "''r''" gives to the proposition "''s''". | 5.15 If ''T<sub>r</sub>'' is the number of the truth-grounds of the proposition "''r''", ''T<sub>r</sub>'' the number of those truth-grounds of the proposition "''s''" which are at the same time truth-grounds of "''r''", then we call the ratio {{nowrap|''T<sub>rs</sub> : T<sub>r</sub>''}} the measure of the ''probability'' which the proposition "''r''" gives to the proposition "''s''". | ||

5.151 Suppose in a schema like that above in No. 5.101 ''T<sub>r</sub>'' is the number of the "T"'s in the proposition ''r'', ''T<sub>rs</sub>'' the number of those "T"'s in the proposition ''s'', which stand in the same columns as "T"'s of the proposition ''r''; then the proposition ''r'' gives to the proposition ''s'' the probability ''T<sub>rs</sub>: T<sub>r</sub> | 5.151 Suppose in a schema like that above in No. 5.101 ''T<sub>r</sub>'' is the number of the "T"'s in the proposition ''r'', ''T<sub>rs</sub>'' the number of those "T"'s in the proposition ''s'', which stand in the same columns as "T"'s of the proposition ''r''; then the proposition ''r'' gives to the proposition ''s'' the probability {{nowrap|''T<sub>rs</sub> : T<sub>r</sub>''}}. | ||

5.1511 There is no special object peculiar to probability propositions. | 5.1511 There is no special object peculiar to probability propositions. | ||

| Line 1,086: | Line 1,086: | ||

So ''this'' is not a mathematical fact. | So ''this'' is not a mathematical fact. | ||

If then, I say, It is equally probable that I should draw a white and a black ball, this means, All the circumstances known to me (including the natural laws hypothetically assumed) give to the occurrence of the one event no more probability than to the occurrence of the other. That is they give — as can easily be | If then, I say, It is equally probable that I should draw a white and a black ball, this means, All the circumstances known to me (including the natural laws hypothetically assumed) give to the occurrence of the one event no more probability than to the occurrence of the other. That is they give — as can easily be understood from the above explanations — to each the probability ½. | ||

What I can verify by the experiment is that the occurrence of the two events is independent of the circumstances with which I have no closer acquaintance. | What I can verify by the experiment is that the occurrence of the two events is independent of the circumstances with which I have no closer acquaintance. | ||

| Line 1,102: | Line 1,102: | ||

5.2 The structures of propositions stand to one another in internal relations. | 5.2 The structures of propositions stand to one another in internal relations. | ||

5.21 We can bring out these internal relations in our manner of expression, by presenting a | 5.21 We can bring out these internal relations in our manner of expression, by presenting a proposition as the result of an operation which produces it from other propositions (the bases of the operation). | ||

5.22 The operation is the expression of a relation between the structures of its result and its bases. | 5.22 The operation is the expression of a relation between the structures of its result and its bases. | ||

| Line 1,156: | Line 1,156: | ||

5.3 All propositions are results of truth-operations on the elementary propositions. | 5.3 All propositions are results of truth-operations on the elementary propositions. | ||

The truth - operation is the way in which a truth - function arises from elementary propositions. | The truth-operation is the way in which a truth-function arises from elementary propositions. | ||

According to the nature of truth-operations, in the same way as out of elementary propositions arise their truth-functions, from truth-functions arises a new one. Every truth-operation creates from truth-functions of elementary propositions another truth-function of elementary propositions, ''i.e.'', a proposition. The result of every truth-operation on the results of truth-operations on elementary propositions is also the result of ''one'' truth-operation on elementary propositions. | According to the nature of truth-operations, in the same way as out of elementary propositions arise their truth-functions, from truth-functions arises a new one. Every truth-operation creates from truth-functions of elementary propositions another truth-function of elementary propositions, ''i.e.'', a proposition. The result of every truth-operation on the results of truth-operations on elementary propositions is also the result of ''one'' truth-operation on elementary propositions. | ||

Revision as of 10:50, 16 January 2021

Dedicated

to the memory of my friend

DAVID H. PINSENT

Kürnberger.

Preface

This book will perhaps only be understood by those who have themselves already thought the thoughts which are expressed in it—or similar thoughts. It is therefore not a text-book. Its object would be attained if there were one person who read it with understanding and to whom it afforded pleasure.

The book deals with the problems of philosophy and shows, as I believe, that the method of formulating these problems rests on the misunderstanding of the logic of our language. Its whole meaning could be summed up somewhat as follows: What can be said at all can be said clearly; and whereof one cannot speak thereof one must be silent.

The book will, therefore, draw a limit to thinking, or rather—not to thinking, but to the expression of thoughts; for, in order to draw a limit to thinking we should have to be able to think both sides of this limit (we should therefore have to be able to think what cannot be thought).

The limit can, therefore, only be drawn in language and what lies on the other side of the limit will be simply nonsense.

How far my efforts agree with those of other philosophers I will not decide. Indeed what I have here written makes no claim to novelty in points of detail; and therefore I give no sources, because it is indifferent to me whether what I have thought has already been thought before me by another.

I will only mention that to the great works of Frege and the writings of my friend Bertrand Russell I owe in large measure the stimulation of my thoughts.

If this work has a value it consists in two things. First that in it thoughts are expressed, and this value will be the greater the better the thoughts are expressed. The more the nail has been hit on the head.— Here I am conscious that I have fallen far short of the possible. Simply because my powers are insufficient to cope with the task.—May others come and do it better.

On the other hand the truth of the thoughts communicated here seems to me unassailable and definitive. I am, therefore, of the opinion that the problems have in essentials been finally solved. And if I am not mistaken in this, then the value of this work secondly consists in the fact that it shows how little has been done when these problems have been solved.

1 The world is everything that is the case.

1.1 The world is the totality of facts, not of things.

1.11 The world is determined by the facts, and by these being all the facts.

1.12 For the totality of facts determines both what is the case, and also all that is not the case.

1.13 The facts in logical space are the world.

1.2 The world divides into facts.

1.21 Any one can either be the case or not be the case, and everything else remain the same.

2 What is the case, the fact, is the existence of atomic facts.

2.01 An atomic fact is a combination of objects (entities, things).

2.011 It is essential to a thing that it can be a constituent part of an atomic fact.

2.012 In logic nothing is accidental: if a thing can occur in an atomic fact the possibility of that atomic fact must already be prejudged in the thing.

2.0121 It would, so to speak, appear as an accident, when to a thing that could exist alone on its own account, subsequently a state of affairs could be made to fit.

If things can occur in atomic facts, this possibility must already lie in them.

(A logical entity cannot be merely possible. Logic treats of every possibility, and all possibilities are its facts.)

Just as we cannot think of spatial objects at all apart from space, or temporal objects apart from time, so we cannot think of any object apart from the possibility of its connexion with other things.

If I can think of an object in the context of an atomic fact, I cannot think of it apart from the possibility of this context.

2.0122 The thing is independent, in so far as it can occur in all possible circumstances, but this form of independence is a form of connexion with the atomic fact, a form of dependence. (It is impossible for words to occur in two different ways, alone and in the proposition.)

2.0123 If I know an object, then I also know all the possibilities of its occurrence in atomic facts.

(Every such possibility must lie in the nature of the object.)

A new possibility cannot subsequently be found.

2.01231 In order to know an object, I must know not its external but all its internal qualities.

2.0124 If all objects are given, then thereby are all possible atomic facts also given.

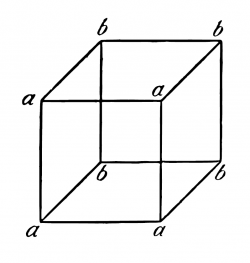

2.013 Every thing is, as it were, in a space of possible atomic facts. I can think of this space as empty, but not of the thing without the space.

2.0131 A spatial object must lie in infinite space. (A point in space is an argument place.)

A speck in a visual field need not be red, but it must have a colour; it has, so to speak, a colour space round it. A tone must have a pitch, the object of the sense of touch a hardness, etc.

2.014 Objects contain the possibility of all states of affairs.

2.0141 The possibility of its occurrence in atomic facts is the form of the object.

2.02 The object is simple.

2.0201 Every statement about complexes can be analysed into a statement about their constituent parts, and into those propositions which completely describe the complexes.

2.021 Objects form the substance of the world. Therefore they cannot be compound.

2.0211 If the world had no substance, then whether a proposition had sense would depend on whether another proposition was true.

2.0212 It would then be impossible to form a picture of the world (true or false).

2.022 It is clear that however different from the real one an imagined world may be, it must have something—a form—in common with the real world.

2.023 This fixed form consists of the objects.

2.0231 The substance of the world can only determine a form and not any material properties. For these are first presented by the propositions—first formed by the configuration of the objects.

2.0232 Roughly speaking: objects are colourless.

2.0233 Two objects of the same logical form are—apart from their external properties—only differentiated from one another in that they are different.

2.02331 Either a thing has properties which no other has, and then one can distinguish it straight away from the others by a description and refer to it; or, on the other hand, there are several things which have the totality of their properties in common, and then it is quite impossible to point to any one of them.

For if a thing is not distinguished by anything, I cannot distinguish it—for otherwise it would be distinguished.

2.024 Substance is what exists independently of what is the case.

2.025 It is form and content.

2.0251 Space, time and colour (colouredness) are forms of objects.

2.026 Only if there are objects can there be a fixed form of the world.

2.027 The fixed, the existent and the object are one.

2.0271 The object is the fixed, the existent; the configuration is the changing, the variable.

2.0272 The configuration of the objects forms the atomic fact.

2.03 In the atomic fact objects hang one in another, like the links of a chain.

2.031 In the atomic fact the objects are combined in a definite way.

2.032 The way in which objects hang together in the atomic fact is the structure of the atomic fact.

2.033 The form is the possibility of the structure.

2.034 The structure of the fact consists of the structures of the atomic facts.

2.04 The totality of existent atomic facts is the world.

2.05 The totality of existent atomic facts also determines which atomic facts do not exist.

2.06 The existence and non-existence of atomic facts is the reality.

(The existence of atomic facts we also call a positive fact, their non-existence a negative fact.)

2.061 Atomic facts are independent of one another.

2.062 From the existence of non-existence of an atomic fact we cannot infer the existence or non-existence of another.

2.063 The total reality is the world.

2.1 We make to ourselves pictures of facts.

2.11 The picture presents the facts in logical space, the existence and non-existence of atomic facts.

2.12 The picture is a model of reality.

2.13 To the objects correspond in the picture the elements of the picture.

2.131 The elements of the picture stand, in the picture, for the objects.

2.14 The picture consists in the fact that its elements are combined with one another in a definite way.

2.141 The picture is a fact.

2.15 That the elements of the picture are combined with one another in a definite way, represents that the things are so combined with one another.

This connexion of the elements of the picture is called its structure, and the possibility of this structure is called the form of representation of the picture.

2.151 The form of representation is the possibility that the things are combined with one another as are the elements of the picture.

2.1511 Thus the picture is linked with reality; it reaches up to it.

2.1512 It is like a scale applied to reality.

2.15121 Only the outermost points of the dividing lines touch the object to be measured.

2.1513 According to this view the representing relation which makes it a picture, also belongs to the picture.

2.1514 The representing relation consists of the co-ordinations of the elements of the picture and the things.

2.1515 These co-ordinations are as it were the feelers of its elements with which the picture touches reality.

2.16 In order to be a picture a fact must have something in common with what it pictures.

2.161 In the picture and the pictured there must be something identical in order that the one can be a picture of the other at all.

2.17 What the picture must have in common with reality in order to be able to represent it after its manner—rightly or falsely—is its form of representation.

2.171 The picture can represent every reality whose form it has.

The spatial picture, everything spatial, the coloured, everything coloured, etc.

2.172 The picture, however, cannot represent its form of representation; it shows it forth.

2.173 The picture represents its object from without (its standpoint is its form of representation), therefore the picture represents its object rightly or falsely.

2.174 But the picture cannot place itself outside of its form of representation.

2.18 What every picture, of whatever form, must have in common with reality in order to be able to represent it at all—rightly or falsely—is the logical form, that is, the form of reality.

2.181 If the form of representation is the logical form, then the picture is called a logical picture.

2.182 Every picture is also a logical picture. (On the other hand, for example, not every picture is spatial.)

2.19 The logical picture can depict the world.

2.2 The picture has the logical form of representation in common with what it pictures.

2.201 The picture depicts reality by representing a possibility of the existence and non-existence of atomic facts.

2.202 The picture represents a possible state of affairs in logical space.

2.203 The picture contains the possibility of the state of affairs which it represents.

2.21 The picture agrees with reality or not; it is right or wrong, true or false.

2.22 The picture represents what it represents, independently of its truth or falsehood, through the form of representation.

2.221 What the picture represents is its sense.

2.222 In the agreement or disagreement of its sense with reality, its truth or falsity consists.

2.223 In order to discover whether the picture is true or false we must compare it with reality.

2.224 It cannot be discovered from the picture alone whether it is true or false.

2.225 There is no picture which is a priori true.

3 The logical picture of the facts is the thought.

3.001 “An atomic fact is thinkable”—means: we can imagine it.

3.01 The totality of true thoughts is a picture of the world.

3.02 The thought contains the possibility of the state of affairs which it thinks.

What is thinkable is also possible.

3.03 We cannot think anything unlogical, for otherwise we should have to think unlogically.

3.031 It used to be said that God could create everything, except what was contrary to the laws of logic. The truth is, we could not say of an “unlogical” world how it would look.

3.032 To present in language anything which “contradicts logic” is as impossible as in geometry to present by its co-ordinates a figure which contradicts the laws of space; or to give the co-ordinates of a point which does not exist.

3.0321 We could present spatially an atomic fact which contradicted the laws of physics, but not one which contradicted the laws of geometry.

3.04 An a priori true thought would be one whose possibility guaranteed its truth.

3.05 Only if we could know a priori that a thought is true if its truth was to be recognized from the thought itself (without an object of comparison).

3.1 In the proposition the thought is expressed perceptibly through the senses.

3.11 We use the sensibly perceptible sign (sound or written sign, etc.) of the proposition as a projection of the possible state of affairs.

The method of projection is the thinking of the sense of the proposition.

3.12 The sign through which we express the thought I call the propositional sign. And the proposition is the propositional sign in its projective relation to the world.

3.13 To the proposition belongs everything which belongs to the projection; but not what is projected.

Therefore the possibility of what is projected but not this itself.

In the proposition, therefore, its sense is not yet contained, but the possibility of expressing it.

(“The content of the proposition” means the content of the significant proposition.)

In the proposition the form of its sense is contained, but not its content.

3.14 The propositional sign consists in the fact that its elements, the words, are combined in it in a definite way.

The propositional sign is a fact.

3.141 The proposition is not a mixture of words (just as the musical theme is not a mixture of tones).

The proposition is articulate.

3.142 Only facts can express a sense, a class of names cannot.

3.143 That the propositional sign is a fact is concealed by the ordinary form of expression, written or printed.

(For in the printed proposition, for example, the sign of a proposition does not appear essentially different from a word. Thus it was possible for Frege to call the proposition a compounded name.)

3.1431 The essential nature of the propositional sign becomes very clear when we imagine it made up of spatial objects (such as tables, chairs, books) instead of written signs.

The mutual spatial position of these things then expresses the sense of the proposition.

3.1432 We must not say, “The complex sign ‘aRb’ says ‘a stands in relation R to b’”; but we must say, “That ‘a’ stands in a certain relation to ‘b’ says that aRb”.

3.144 States of affairs can be described but not named.

(Names resemble points; propositions resemble arrows, they have sense.)

3.2 In propositions thoughts can be so expressed that to the objects of the thoughts correspond the elements of the propositional sign.

3.201 These elements I call “simple signs” and the proposition “completely analysed”.

3.202 The simple signs employed in propositions are called names.

3.203 The name means the object. The object is its meaning. (“A” is the same sign as “A”.)

3.21 To the configuration of the simple signs in the propositional sign corresponds the configuration of the objects in the state of affairs.

3.22 In the proposition the name represents the object.

3.221 Objects I can only name. Signs represent them. I can only speak of them. I cannot assert them. A proposition can only say how a thing is, not what it is.

3.23 The postulate of the possibility of the simple signs is the postulate of the determinateness of the sense.

3.24 A proposition about a complex stands in internal relation to the proposition about its constituent part.

A complex can only be given by its description, and this will either be right or wrong. The proposition in which there is mention of a complex, if this does not exist, becomes not nonsense but simply false.

That a propositional element signifies a complex can be seen from an indeterminateness in the propositions in which it occurs. We know that everything is not yet determined by this proposition. (The notation for generality contains a prototype.)

The combination of the symbols of a complex in a simple symbol can be expressed by a definition.

3.25 There is one and only one complete analysis of the proposition.

3.251 The proposition expresses what it expresses in a definite and clearly specifiable way: the proposition is articulate.

3.26 The name cannot be analysed further by any definition. It is a primitive sign.

3.261 Every defined sign signifies via those signs by which it is defined, and the definitions show the way.

Two signs, one a primitive sign, and one defined by primitive signs, cannot signify in the same way. Names cannot be taken to pieces by definition (nor any sign which alone and independently has a meaning).

3.262 What does not get expressed in the sign is shown by its application. What the signs conceal, their application declares.

3.263 The meanings of primitive signs can be explained by elucidations. Elucidations are propositions which contain the primitive signs. They can, therefore, only be understood when the meanings of these signs are already known.

3.3 Only the proposition has sense; only in the context of a proposition has a name meaning.

3.31 Every part of a proposition which characterizes its sense I call an expression (a symbol).

(The proposition itself is an expression.)

Expressions are everything—essential for the sense of the proposition—that propositions can have in common with one another.

An expression characterizes a form and a content.

3.311 An expression presupposes the forms of all propositions in which it can occur. It is the common characteristic mark of a class of propositions.

3.312 It is therefore represented by the general form of the propositions which it characterizes.

And in this form the expression is constant and everything else variable.

3.313 An expression is thus presented by a variable, whose values are the propositions which contain the expression.

(In the limiting case the variable becomes constant, the expression a proposition.)

I call such a variable a “propositional variable”.

3.314 An expression has meaning only in a proposition. Every variable can be conceived as a propositional variable. (Including the variable name.)

3.315 If we change a constituent part of a proposition into a variable, there is a class of propositions which are all the values of the resulting variable proposition. This class in general still depends on what, by arbitrary agreement, we mean by parts of that proposition. But if we change all those signs, whose meaning was arbitrarily determined, into variables, there always remains such a class. But this is now no longer dependent on any agreement; it depends only on the nature of the proposition. It corresponds to a logical form, to a logical prototype.

3.316 What values the propositional variable can assume is determined.

The determination of the values is the variable.

3.317 The determination of the values of the propositional variable is done by indicating the propositions whose common mark the variable is.

The determination is a description of these propositions.

The determination will therefore deal only with symbols not with their meaning.

And only this is essential to the determination, that it is only a description of symbols and asserts nothing about what is symbolized.

The way in which we describe the propositions is not essential.

3.318 I conceive the proposition—like Frege and Russell—as a function of the expressions contained in it.

3.32 The sign is the part of the symbol perceptible by the senses.

3.321 Two different symbols can therefore have the sign (the written sign or the sound sign) in common—they then signify in different ways.

3.322 It can never indicate the common characteristic of two objects that we symbolize them with the same signs but by different methods of symbolizing. For the sign is arbitrary. We could therefore equally well choose two different signs and where then would be what was common in the symbolization.

3.323 In the language of everyday life it very often happens that the same word signifies in two different ways—and therefore belongs to two different symbols—or that two words, which signify in different ways, are apparently applied in the same way in the proposition.

Thus the word "is" appears as the copula, as the sign of equality, and as the expression of existence; "to exist" as an intransitive verb like "to go"; "identical" as an adjective; we speak of something but also of the fact of something happening.

(In the proposition "Green is green"—where the first word is a proper name as the last an adjective—these words have not merely different meanings but they are different symbols.)

3.324 Thus there easily arise the most fundamental confusions (of which the whole of philosophy is full).

3.325 In order to avoid these errors, we must employ a symbolism which excludes them, by not applying the same sign in different symbols and by not applying signs in the same way which signify in different ways. A symbolism, that is to say, which obeys the rules of logical grammar—of logical syntax.

(The logical symbolism of Frege and Russell is such a language, which, however, does still not exclude all errors.)

3.326 In order to recognize the symbol in the sign we must consider the significant use.

3.327 The sign determines a logical form only together with its logical syntactic application.

3.328 If a sign is not necessary then it is meaningless. That is the meaning of Occam’s razor.

(If everything in the symbolism works as though a sign had meaning, then it has meaning.)

3.33 In logical syntax the meaning of a sign ought never to play a rôle; it must admit of being established without mention being thereby made of the meaning of a sign; it ought to presuppose only the description of the expressions.

3.331 From this observation we get a further view—into Russell’s Theory of Types. Russell’s error is shown by the fact that in drawing up his symbolic rules he has to speak about the things his signs mean.

3.332 No proposition can say anything about itself, because the propositional sign cannot be contained in itself (that is the “whole theory of types”).

3.333 A function cannot be its own argument, because the functional sign already contains the prototype of its own argument and it cannot contain itself.

If, for example, we suppose that the function F(fx) could be its own argument, then there would be a proposition “F(F(fx))”, and in this the outer function F and the inner function F must have different meanings; for the inner has the form ϕ(fx), the outer the form ψ(ϕ(fx)). Common to both functions is only the letter “F”, which by itself signifies nothing.

This is at once clear, if instead of “F(F(u))” we write “(∃ϕ):F(ϕu).ϕu=Fu”.

Herewith Russell’s paradox vanishes.

3.334 The rules of logical syntax must follow of themselves, if we only know how every single sign signifies.

3.34 A proposition possesses essential and accidental features.

Accidental are the features which are due to a particular way of producing the propositional sign. Essential are those which alone enable the proposition to express its sense.

3.341 The essential in a proposition is therefore that which is common to all propositions which can express the same sense.

And in the same way in general the essential in a symbol is that which all symbols which can fulfil the same purpose have in common.

3.3411 One could therefore say the real name is that which all symbols, which signify an object, have in common. It would then follow, step by step, that no sort of composition was essential for a name.

3.342 In our notations there is indeed something arbitrary, but this is not arbitrary, namely that if we have determined anything arbitrarily, then something else must be the case. (This results from the essence of the notation.)

3.3421 A particular method of symbolizing may be unimportant, but it is always important that this is a possible method of symbolizing. And this happens as a rule in philosophy: The single thing proves over and over again to be unimportant, but the possibility of every single thing reveals something about the nature of the world.

3.343 Definitions are rules for the translation of one language into another. Every correct symbolism must be translatable into every other according to such rules. It is this which all have in common.

3.344 What signifies in the symbol is what is common to all those symbols by which it can be replaced according to the rules of logical syntax.

3.3441 We can, for example, express what is common to all notations for the truth-functions as follows: It is common to them that they all, for example, can be replaced by the notations of “~p” (“not p”) and “p∨q” (“p or q”).

(Herewith is indicated the way in which a special possible notation can give us general information.)

3.3442 The sign of the complex is not arbitrarily resolved in the analysis, in such a way that its resolution would be different in every propositional structure.

3.4 The proposition determines a place in logical space: the existence of this logical place is guaranteed by the existence of the constituent parts alone, by the existence of the significant proposition.

3.41 The propositional sign and the logical co-ordinates: that is the logical place.

3.411 The geometrical and the logical place agree in that each is the possibility of an existence.

3.42 Although a proposition may only determine one place in logical space, the whole logical space must already be given by it.

(Otherwise denial, the logical sum, the logical product, etc., would always introduce new elements—in co-ordination.)

(The logical scaffolding round the picture determines the logical space. The proposition reaches through the whole logical space.)

3.5 The applied, thought, propositional sign, is the thought.

4 The thought is the significant proposition.

4.001 The totality of propositions is the language.

4.002 Man possesses the capacity of constructing languages, in which every sense can be expressed, without having an idea how and what each word means—just as one speaks without knowing how the single sounds are produced.

Colloquial language is a part of the human organism and is not less complicated than it.

From it it is humanly impossible to gather immediately the logic of language.

Language disguises the thought; so that from the external form of the clothes one cannot infer the form of the thought they clothe, because the external form of the clothes is constructed with quite another object than to let the form of the body be recognized.

The silent adjustments to understand colloquial language are enormously complicated.

4.003 Most propositions and questions, that have been written about philosophical matters, are not false, but senseless. We cannot, therefore, answer questions of this kind at all, but only state their senselessness. Most questions and propositions of the philosophers result from the fact that we do not understand the logic of our language.

(They are of the same kind as the question whether the Good is more or less identical than the Beautiful.)

And so it is not to be wondered at that the deepest problems are really no problems.

4.0031 All philosophy is “Critique of language” (but not at all in Mauthner’s sense). Russell’s merit is to have shown that the apparent logical form of the proposition need not be its real form.

4.01 The proposition is a picture of reality.

The proposition is a model of the reality as we think it is.

4.011 At the first glance the proposition—say as it stands printed on paper—does not seem to be picture of the reality of which it treats. But nor does the musical score appear at first sight to be a picture of a musical piece; nor does our phonetic spelling (letters) seem to be a picture of our spoken language. And yet these symbolisms prove to be pictures—even in the ordinary sense of the word—of what they represent.

4.012 It is obvious that we perceive a proposition of the form aRb as a picture. Here the sign is obviously a likeness of the signified.

4.013 And if we penetrate to the essence of this pictorial nature we see that this is not disturbed by apparent irregularities (like the use of ♯ and ♭ in the score).

For these irregularities also picture what they are to express; only in another way.

4.014 The gramophone record, the musical thought, the score, the waves of sound, all stand to one another in that pictorial internal relation, which holds between language and the world.

To all of them the logical structure is common.

(Like the two youths, their two horses and their lilies in the story. They are all in a certain sense one.)

4.0141 In the fact that there is a general rule by which the musician is able to read the symphony out of the score, and that there is a rule by which one could reconstruct the symphony from the line on a gramophone record and from this again—by means of the first rule—construct the score, herein lies the internal similarity between these things which at first sight seem to be entirely different. And the rule is the law of projection which projects the symphony into the language of the musical score. It is the rule of translation of this language into the language of the gramophone record.

4.015 The possibility of all similes, of all the imagery of our language, rests on the logic of representation.

4.016 In order to understand the essence of the proposition, consider hieroglyphic writing, which pictures the facts it describes.

And from it came the alphabet without the essence of the representation being lost.

4.02 This we see from the fact that we understand the sense of the propositional sign, without having had it explained to us.

4.021 The proposition is a picture of reality, for I know the state of affairs presented by it, if I understand the proposition. And I understand the proposition, without its sense having been explained to me.

4.022 The proposition shows its sense.

The proposition shows how things stand, if it is true. And it says, that they do so stand.

4.023 The proposition determines reality to this extent, that one only needs to say “Yes” or “No” to it to make it agree with reality.

Reality must therefore be completely described by the proposition.

A proposition is the description of a fact.

As the description of an object describes it by its external properties so propositions describe reality by its internal properties.

The proposition constructs a world with the help of a logical scaffolding, and therefore one can actually see in the proposition all the logical features possessed by reality if it is true. One can draw conclusions from a false proposition.

4.024 To understand a proposition means to know what is the case, if it is true.

(One can therefore understand it without knowing whether it is true or not.)

One understands it if one understands it constituent parts.

4.025 The translation of one language into another is not a process of translating each proposition of the one into a proposition of the other, but only the constituent parts of propositions are translated.

(And the dictionary does not only translate substantives but also adverbs and conjunctions, etc., and it treats them all alike.)

4.026 The meanings of the simple signs (the words) must be explained to us, if we are to understand them.

By means of propositions we explain ourselves.

4.027 It is essential to propositions, that they can communicate a new sense to us.

4.03 A proposition must communicate a new sense with old words.

The proposition communicates to us a state of affairs, therefore it must be essentially connected with the state of affairs.

And the connexion is, in fact, that it is its logical picture.

The proposition only asserts something, in so far as it is a picture.

4.031 In the proposition a state of affairs is, as it were, put together for the sake of experiment.

One can say, instead of, This proposition has such and such a sense, This proposition represents such and such a state of affairs.

4.0311 One name stands for one thing, and another for another thing, and they are connected together. And so the whole, like a living picture, presents the atomic fact.

4.0312 The possibility of propositions is based upon the principle of the representation of objects by signs.

My fundamental thought is that the “logical constants” do not represent. That the logic of the facts cannot be represented.

4.032 The proposition is a picture of its state of affairs, only in so far as it is logically articulated. (Even the proposition “ambulo” is composite, for its stem gives a different sense with another termination, or its termination with another stem.)

4.04 In the proposition there must be exactly as many thing distinguishable as there are in the state of affairs, which it represents.

They must both possess the same logical (mathematical) multiplicity (cf. Hertz’s Mechanics, on Dynamic Models).

4.041 This mathematical multiplicity naturally cannot in its turn be represented. One cannot get outside it in the representation.

4.0411 If we tried, for example, to express what is expressed by “(x).fx” by putting an index before fx, like: “Gen.fx”, it would not do, we should not know what was generalized. If we tried to show it by an index g, like: “f(xg)” it would not do—we should not know the scope of the generalization.

If we were to try it by introducing a mark in the argument places, like “(G, G).F(G, G)”, it would not do—we could not determine the identity of the variables, etc.

All these ways of symbolizing are inadequate because they have not the necessary mathematical multiplicity.

4.0412 For the same reason the idealist explanation of the seeing of spatial relations through “spatial spectacles” does not do, because it cannot explain the multiplicity of these relations.

4.05 Reality is compared with the proposition.

4.06 Propositions can be true or false only by being pictures of the reality.

4.061 If one does not observe that propositions have a sense independent of the facts, one can easily believe that true and false are two relations between signs and things signified with equal rights.

One could, then, for example, say that “p” signifies in the true way what “~p” signifies in the false way, etc.

4.062 Can we not make ourselves understood by means of false propositions as hitherto with true ones, so long as we know that they are meant to be false? No! For a proposition is true, if what we assert by means of it is the case; and if by “p” we mean ~p, and what we mean is the case, then “p” in the new conception is true and not false.

4.0621 That, however, the signs “p” and “~p” can say the same thing is important, for it shows that the sign “~” corresponds to nothing in reality.

That negation occurs in a proposition, is no characteristic of its sense (~ ~p=p).

The propositions “p” and “~p” have opposite senses, but to them corresponds one and the same reality.

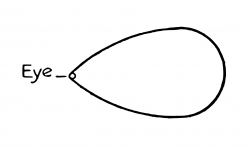

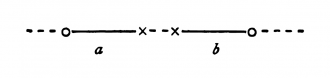

4.063 An illustration to explain the concept of truth. A black spot on white paper; the form of the spot can be described by saying of each point of the plane whether it is white or black. To the fact that a point is black corresponds a positive fact; to the fact that a point is white (not black), a negative fact. If I indicate a point of the plane (a truth-value in Frege’s terminology), this corresponds to the assumption proposed for judgment, etc. etc.

But to be able to say that a point is black or white, I must first know under what conditions a point is called white or black; in order to be able to say “p” is true (or false) I must have determined under what conditions I call “p” true, and thereby I determine the sense of the proposition.

The point at which the simile breaks down is this: we can indicate a point on the paper, without knowing what white and black are; but to a proposition without a sense corresponds nothing at all, for it signifies no thing (truth-value) whose properties are called “false” or “true”; the verb of the proposition is not “is true” or “is false”—as Frege thought—but that which “is true” must already contain the verb.

4.064 Every proposition must already have a sense; assertion cannot give it a sense, for what it asserts is the sense itself. And the same holds of denial, etc.

4.0641 One could say, the denial is already related to the logical place determined by the proposition that is denied.

The denying proposition determines a logical place other than does the proposition denied.

The denying proposition determines a logical place, with the help of the logical place of the proposition denied, by saying that it lies outside the latter place.

That one can deny again the denied proposition, shows that what is denied is already a proposition and not merely the preliminary to a proposition.

4.1 A proposition presents the existence and non-existence of atomic facts.

4.11 The totality of true propositions is the total natural science (or the totality of the natural sciences).

4.111 Philosophy is not one of the natural sciences.

(The word “philosophy” must mean something which stands above or below, but not beside the natural sciences.)

4.112 The object of philosophy is the logical clarification of thoughts.

Philosophy is not a theory but an activity.

A philosophical work consists essentially of elucidations.

The result of philosophy is not a number of “philosophical propositions”, but to make propositions clear.

Philosophy should make clear and delimit sharply the thoughts which otherwise are, as it were, opaque and blurred.

4.1121 Psychology is no nearer related to philosophy, than is any other natural science.

The theory of knowledge is the philosophy of psychology.

Does not my study of sign-language correspond to the study of thought processes which philosophers held to be so essential to the philosophy of logic? Only they got entangled for the most part in unessential psychological investigations, and there is an analogous danger for my method.

4.1122 The Darwinian theory has no more to do with philosophy than has any other hypothesis of natural science.

4.113 Philosophy limits the disputable sphere of natural science.

4.114 It should limit the thinkable and thereby the unthinkable.

It should limit the unthinkable from within through the thinkable.

4.115 It will mean the unspeakable by clearly displaying the speakable.

4.116 Everything that can be thought at all can be thought clearly. Everything that can be said can be said clearly.

4.12 Propositions can represent the whole reality, but they cannot represent what they must have in common with reality in order to be able to represent it—the logical form.

To be able to represent the logical form, we should have to be able to put ourselves with the propositions outside logic, that is outside the world.

4.121 Propositions cannot represent the logical form: this mirrors itself in the propositions.

That which mirrors itself in language, language cannot represent.

That which expresses itself in language, we cannot express by language.

The propositions show the logical form of reality.

They exhibit it.

4.1211 Thus a proposition “fa” shows that in its sense the object a occurs, two propositions “fa” and “ga” that they are both about the same object.

If two propositions contradict one another, this is shown by their structure; similarly if one follows from another, etc.

4.1212 What can be shown cannot be said.

4.1213 Now we understand our feeling that we are in possession of the right logical conception, if only all is right in our symbolism.

4.122 We can speak in a certain sense of formal properties of objects and atomic facts, or of properties of the structure of facts, and in the same sense of formal relations and relations of structures.

(Instead of property of the structure I also say “internal property”; instead of relation of structures “internal relation”.

I introduce these expressions in order to show the reason for the confusion, very widespread among philosophers, between internal relations and proper (external) relations.)

The holding of such internal properties and relations cannot, however, be asserted by propositions, but it shows itself in the propositions, which present the facts and treat of the objects in question.

4.1221 An internal property of a fact we also call a feature of this fact. (In the sense in which we speak of facial features.)

4.123 A property is internal if it is unthinkable that its object does not possess it.

(This blue colour and that stand in the internal relation of brighter and darker eo ipso. It is unthinkable that these two objects should not stand in this relation.)

(Here to the shifting use of the words “property” and “relation” there corresponds the shifting use of the word “object”.)

4.124 The existence of an internal property of a possible state of affairs is not expressed by a proposition, but it expresses itself in the proposition which presents that state of affairs, by an internal property of this proposition.

It would be as senseless to ascribe a formal property to a proposition as to deny it the formal property.

4.1241 One cannot distinguish forms from one another by saying that one has this property, the other that: for this assumes that there is a sense in asserting either property of either form.

4.125 The existence of an internal relation between possible states of affairs expresses itself in language by an internal relation between the propositions presenting them.

4.1251 Now this settles the disputed question “whether all relations are internal or external”.

4.1252 Series which are ordered by internal relations I call formal series.

The series of numbers is ordered not by an external, but by an internal relation.

Similarly the series of propositions “aRb”,

- “(∃x):aRx.xRb”,

- “(∃x,y):aRx.xRy.yRb”, etc.

(If b stands in one of these relations to a, I call b a successor of a.)

4.126 In the sense in which we speak of formal properties we can now speak also of formal concepts.

(I introduce this expression in order to make clear the confusion of formal concepts with proper concepts which runs through the whole of the old logic.)

That anything falls under a formal concept as an object belonging to it, cannot be expressed by a proposition. But it is shown in the symbol for the object itself. (The name shows that it signifies an object, the numerical sign that it signifies a number, etc.)

Formal concepts, cannot, like proper concepts, be presented by a function.

For their characteristics, the formal properties, are not expressed by the functions.

The expression of a formal property is a feature of certain symbols.

The sign that signifies the characteristics of a formal concept is, therefore, a characteristic feature of all symbols, whose meanings fall under the concept. The expression of the formal concept is therefore a propositional variable in which only this characteristic feature is constant.

4.127 The propositional variable signifies the formal concept, and its values signify the objects which fall under this concept.

4.1271 Every variable is the sign of a formal concept.

For every variable presents a constant form, which all its values possess, and which can be conceived as a formal property of these values.

4.1272 So the variable name “x” is the proper sign of the pseudo-concept object.

Wherever the word “object” (“thing”, “entity”, etc.) is rightly used, it is expressed in logical symbolism by the variable name.

For example in the proposition “there are two objects which …”, by “(∃x,y)…”.

Wherever it is used otherwise, i.e. as a proper concept word, there arise senseless pseudo-propositions.

So one cannot, e.g. say “There are objects” as one says “There are books”. Nor “There are 100 objects” or “There are ℵ0 objects”.

And it is senseless to speak of the number of all objects.

The same holds of the words “Complex”, “Fact”, “Function”, “Number”, etc.

They all signify formal concepts and are presented in logical symbolism by variables, not by functions or classes (as Frege and Russell thought).

Expressions like “1 is a number”, “there is only one number nought”, and all like them are senseless.

(It is as senseless to say, “there is only one 1” as it would be to say: 2+2 is at 3 o’clock equal to 4.)

4.12721 The formal concept is already given with an object, which falls under it. One cannot, therefore, introduce both, the objects which fall under a formal concept and the formal concept itself, as primitive ideas. One cannot, therefore, e.g. introduce (as Russell does) the concept of function and also special functions as primitive ideas; or the concept of number and definite numbers.

4.1273 If we want to express in logical symbolism the general proposition “b is a successor of a” we need for this an expression for the general term of the formal series: aRb, (∃x):aRx.xRb, (∃x,y):aRx.xRy.yRb,… The general term of a formal series can only be expressed by a variable, for the concept symbolized by “term of this formal series” is a formal concept. (This Frege and Russell overlooked; the way in which they express general propositions like the above is, therefore, false; it contains a vicious circle.)

We can determine the general term of the formal series by giving its first term and the general form of the operation, which generates the following term out of the preceding proposition.

4.1274 The question about the existence of a formal concept is senseless. For no proposition can answer such a question.

(For example, one cannot ask: “Are there unanalysable subject-predicate propositions?”)

4.128 The logical forms are anumerical.

Therefore there are in logic no pre-eminent numbers, and therefore there is no philosophical monism or dualism, etc.

4.2 The sense of a proposition is its agreement and disagreement with the possibilities of the existence and non-existence of the atomic facts.

4.21 The simplest proposition, the elementary proposition, asserts the existence of an atomic fact.

4.211 It is a sign of an elementary proposition, that no elementary proposition can contradict it.

4.22 The elementary proposition consists of names. It is a connexion, a concatenation, of names.

4.221 It is obvious that in the analysis of propositions we must come to elementary propositions, which consist of names in immediate combination.

The question arises here, how the propositional connexion comes to be.

4.2211 Even if the world is infinitely complex, so that every fact consists of an infinite number of atomic facts and every atomic fact is composed of an infinite number of objects, even then there must be objects and atomic facts.

4.23 The name occurs in the proposition only in the context of the elementary proposition.

4.24 The names are the simple symbols, I indicate them by single letters (x, y, z).

The elementary proposition I write as function of the names, in the form “fx”, “ϕ(x,y)”, etc.

Or I indicate it by the letters p, q, r.

4.241 If I use two signs with one and the same meaning, I express this by putting between them the sign “=”.

“a=b” means then, that the sign “a” is replaceable by the sign “b”.

(If I introduce by an equation a new sign “b”, by determining that it shall replace a previously known sign “a”, I write the equation—definition —(like Russell) in the form “a=b Def.”. A definition is a symbolic rule.)

4.242 Expressions of the form “a=b” are therefore only expedients in presentation: They assert nothing about the meaning of the signs “a” and “b”.

4.243 Can we understand two names without knowing whether they signify the same thing or two different things? Can we understand a proposition in which two names occur, without knowing if they mean the same or different things?

If I know the meaning of an English and a synonymous German word, it is impossible for me not to know that they are synonymous, it is impossible for me not to be able to translate them into one another.

Expressions like “a=a”, or expressions deduced from these are neither elementary propositions nor otherwise significant signs. (This will be shown later.)

4.25 If the elementary proposition is true, the atomic fact exists; if it is false the atomic fact does not exist.

4.26 The specification of all true elementary propositions describes the world completely. The world is completely described by the specification of all elementary propositions plus the specification, which of them are true and which false.

4.27 With regard to the existence of n atomic facts there are [math]\displaystyle{ K_n = \sum_{v=0}^n \binom{n}{v} }[/math] possibilities.

It is possible for all combinations of atomic facts to exist, and the others not to exist.

4.28 To these combinations correspond the same number of possibilities of the truth—and falsehood—of n elementary propositions.

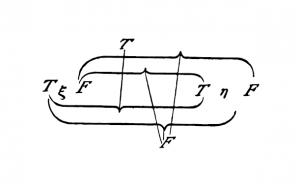

4.3 The truth-possibilities of the elementary propositions mean the possibilities of the existence and non-existence of the atomic facts. 4.31 The truth-possibilities can be presented by schemata of the following kind ("T" means "true", "F" "false". The rows of T's and F's under the row of the elementary propositions mean their truth-possibilities in an easily intelligible symbolism).

| p | q | r |

|---|---|---|

| T | T | T |

| F | T | T |

| T | F | T |

| T | T | F |

| F | F | T |

| F | T | F |

| T | F | F |

| F | F | F |

| p | q |

|---|---|

| T | T |

| F | T |

| T | F |

| F | F |

| p |

|---|

| T |

| F |

4.4 A proposition is the expression of agreement and disagreement with the truth-possibilities of the elementary propositions.

4.41 The truth-possibilities of the elementary propositions are the conditions of the truth and falsehood of the propositions.

4.411 It seems probable even at first sight that the introduction of the elementary propositions is fundamental for the comprehension of the other kinds of propositions. Indeed the comprehension of the general propositions depends palpably on that of the elementary propositions.

4.42 With regard to the agreement and disagreement of a proposition with the truth-possibilities of n elementary propositions there are [math]\displaystyle{ \sum_{k=0}^{K_n} \binom{K_n}{k} = L_n }[/math] possibilities.

Agreement with the truth-possibilities can be expressed by co-ordinating with them in the schema the mark "T" (true).

Absence of this mark means disagreement.

4.431 The expression of the agreement and disagreement with the truth-possibilities of the elementary-propositions expresses the truth-conditions of the proposition. The proposition is the expression of its truth-conditions.

(Frege has therefore quite rightly put them at the beginning, as explaining the signs of his logical symbolism. Only Frege's explanation of the truth-concept is false: if "the true" and "the false" were real objects and the arguments in ~p etc., then the sense of ~p would by no means be determined by Frege's determination.)

4.44 The sign which arises from the co-ordination of that mark "T" with the truth-possibilities is a propositional sign.

4.441 It is clear that to the complex of the signs "F" and "T" no object (or complex of objects) corresponds; any more than to horizontal and vertical lines or to brackets. There are no "logical objects".

Something analogous holds of course for all signs, which express the same as the schemata of "T"and "F".

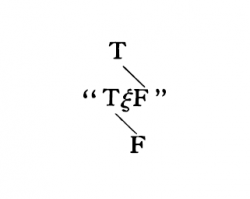

4.442 Thus e.g.

| " |

|

" |

is a propositional sign.

(Frege's assertion sign "[math]\displaystyle{ \vdash }[/math]" is logically altogether meaningless; in Frege (and Russell) it only shows that these authors hold as true the propositions marked in this way.

"[math]\displaystyle{ \vdash }[/math]" belongs therefore to the propositions no more than does the number of the proposition. A proposition cannot possibly assert of itself that it is true.)

If the sequence of the truth-possibilities in the schema is once for all determined by a rule of combination, then the last column is by itself an expression of the truth-conditions. If we write this column as a row the propositional sign becomes: "(T—T) (p,q)" or more plainly: "(T T F T) (p,q)".

(The number of places in the left-hand bracket is determined by the number of terms in the right-hand bracket.)

4.45 For n elementary propositions there are Ln possible groups of truth-conditions.

The groups of truth-conditions which belong to the truth-possibilities of a number of elementary propositions can be ordered in a series.

4.46 Among the possible groups of truth-conditions there are two extreme cases.

In the one case the proposition is true for all the truth-possibilities of the elementary propositions. We say that the truth-conditions are tautological.

In the second case the proposition is false for all the truth-possibilities. The truth-conditions are self-contradictory.

In the first case we call the proposition a tautology, in the second case a contradiction.

4.461 The proposition shows what it says, the tautology and the contradiction that they say nothing.

The tautology has no truth-conditions, for it is unconditionally true; and the contradiction is on no condition true.

Tautology and contradiction are without sense.

(Like the point from which two arrows go out in opposite directions.)

(I know, e.g. nothing about the weather, when I know that it rains or does not rain.)

4.4611 Tautology and contradiction are, however, not nonsensical; they are part of the symbolism, in the same way that "0" is part of the symbolism of Arithmetic.

4.462 Tautology and contradiction are not pictures of the reality. They present no possible state of affairs. For the one allows every possible state of affairs, the other none.

In the tautology the conditions of agreement with the world — the presenting relations — cancel one another, so that it stands in no presenting relation to reality.

4.463 The truth-conditions determine the range, which is left to the facts by the proposition.

(The proposition, the picture, the model, are in a negative sense like a solid body, which restricts the free movement of another: in a positive sense, like the space limited by solid substance, in which a body may be placed.)

Tautology leaves to reality the whole infinite logical space; contradiction fills the whole logical space and leaves no point to reality. Neither of them, therefore, can in any way determine reality.

4.464 The truth of tautology is certain, of propositions possible, of contradiction impossible.

(Certain, possible, impossible: here we have an indication of that gradation which we need in the theory of probability.)

4.465 The logical product of a tautology and a proposition says the same as the proposition. Therefore that product is identical with the proposition. For the essence of the symbol cannot be altered without altering its sense.

4.466 To a definite logical combination of signs corresponds a definite logical combination of their meanings; every arbitrary combination only corresponds to the unconnected signs.

That is, propositions which are true for every state of affairs cannot be combinations of signs at all, for otherwise there could only correspond to them definite combinations of objects.

(And to no logical combination corresponds no combination of the objects.)

Tautology and contradiction are the limiting cases of the combinations of symbols, namely their dissolution.

4.4661 Of course the signs are also combined with one another in the tautology and contradiction, i.e. they stand in relations to one another, but these relations are meaningless, unessential to the symbol.

4.5 Now it appears to be possible to give the most general form of proposition; i.e. to give a description of the propositions of some one sign language, so that every possible sense can be expressed by a symbol, which falls under the description, and so that every symbol which falls under the description can express a sense, if the meanings of the names are chosen accordingly.

It is clear that in the description of the most general form of proposition only what is essential to it may be described — otherwise it would not be the most general form.

That there is a general form is proved by the fact that there cannot be a proposition whose form could not have been foreseen (i.e. constructed). The general form of proposition is: Such and such is the case.

4.51 Suppose all elementary propositions were given me: then we can simply ask: what propositions I can build out of them. And these are all propositions and so are they limited.

4.52 The propositions are everything which follows from the totality of all elementary propositions (of course also from the fact that it is the totality of them all). (So, in some sense, one could say, that all propositions are generalizations of the elementary propositions.)

4.53 The general propositional form is a variable.

5 Propositions are truth-functions of elementary propositions.

(An elementary proposition is a truth-function of itself.)

5.01 The elementary propositions are the truth-arguments of propositions.

5.02 It is natural to confuse the arguments of functions with the indices of names. For I recognize the meaning of the sign containing it from the argument just as much as from the index.

In Russell's "+c", for example, "c" is an index which indicates that the whole sign is the addition sign for cardinal numbers. But this way of symbolizing depends on arbitrary agreement, and one could choose a simple sign instead of "+c": but in "~p" "p" is not an index but an argument; the sense of "~p" cannot be understood, unless the sense of "p" has previously been understood. (In the name Julius Caesar, Julius is an index. The index is always part of a description of the object to whose name we attach it, e.g. The Caesar of the Julian gens.)

The confusion of argument and index is, if I am not mistaken, at the root of Frege's theory of the meaning of propositions and functions. For Frege the propositions of logic were names and their arguments the indices of these names.

5.1 The truth-functions can be ordered in series. That is the foundation of the theory of probability.

5.101 The truth-functions of every number of elementary propositions can be written in a schema of the following kind:

| (TTTT)(p, q) | Tautology | (if p then p, and if q then q.) [p ⊃ p . q ⊃ q] |

| (FTTT)(p, q) | in words: | Not both p and q. [~(p . q)] |

| (TFTT)(p, q) | „ „ | If q then p. [q ⊃ p] |

| (TTFT)(p, q) | „ „ | If p then q. [p ⊃ q] |

| (TTTF)(p, q) | „ „ | p or q. [p ∨ q] |

| (FFTT)(p, q) | „ „ | Not q. ~q |

| (FTFT)(p, q) | „ „ | Not p. ~p |

| (FTTF)(p, q) | „ „ | p or q, but not both. [p . ~q : ∨ : q . ~p] |

| (TFFT)(p, q) | „ „ | If p, then q; and if q, then p. [p ≡ q] |

| (TFTF)(p, q) | „ „ | p |

| (TTFF)(p, q) | „ „ | q |

| (FFFT)(p, q) | „ „ | Neither p nor q. [~p . ~q or p | q] |

| (FFTF)(p, q) | „ „ | p and not q. [p . ~q] |

| (FTFF)(p, q) | „ „ | q and not p. [q . ~p] |

| (TFFF)(p, q) | „ „ | q and p. [q . p] |

| (FFFF)(p, q) | Contradiction | (p and not p; and q and not q.) [p . ~p . q . ~q] |

5.11 If the truth-grounds which are common to a number of propositions are all also truth-grounds of some one proposition, we say that the truth of this proposition follows from the truth of those propositions.

5.12 In particular the truth of a proposition p follows from that of a proposition q, if all the truth-grounds of the second are truth-grounds of the first.

5.121 The truth-grounds of q are contained in those of p; p follows from q.

5.122 If p follows from q, the sense of "p" is contained in that of "q".

5.123 If a god creates a world in which certain propositions are true, he creates thereby also a world in which all propositions consequent on them are true. And similarly he could not create a world in which the proposition "p" is true without creating all its objects.

5.124 A proposition asserts every proposition which follows from it.

5.1241 "p.q" is one of the propositions which assert "p" and at the same time one of the propositions which assert "q".

Two propositions are opposed to one another if there is no significant proposition which asserts them both.

Every proposition which contradicts another, denies it.

5.13 That the truth of one proposition follows from the truth of other propositions, we perceive from the structure of the propositions.

5.131 If the truth of one proposition follows from the truth of others, this expresses itself in relations in which the forms of these propositions stand to one another, and we do not need to put them in these relations first by connecting them with one another in a proposition; for these relations are internal, and exist as soon as, and by the very fact that, the propositions exist.

5.1311 When we conclude from pvq and ~p to q the relation between the forms of the propositions "pvq" and "~p" is here concealed by the method of symbolizing. But if we write, e.g. instead of "pvq" "p|q .|. p|q" and instead of "~p" "p|p" (p|q = neither p nor q), then the inner connexion becomes obvious.

(The fact that we can infer fa from (x)fx shows that generality is present also in the symbol "(x).fx".

5.132 If p follows from q, I can conclude from qp to p; infer p from q.

The method of inference is to be understood from the two propositions alone.

Only they themselves can justify the inference.

Laws of inference, which — as in Frege and Russell — are to justify the conclusions, are senseless and would be superfluous.

5.133 All inference takes place a priori.

5.134 From an elementary proposition no other can be inferred.

5.135 In no way can an inference be made from the existence of one state of affairs to the existence of another entirely different from it.

5.136 There is no causal nexus which justifies such an inference.

5.1361 The events of the future cannot be inferred from those of the present.

Superstition is the belief in the causal nexus.

5.1362 The freedom of the will consists in the fact that future actions cannot be known now. We could only know them if causality were an inner necessity, like that of logical deduction. — The connexion of knowledge and what is known is that of logical necessity.

("A knows that p is the case*' is senseless if p is a tautology.)

5.1363 If from the fact that a proposition is obvious to us it does not follow that it is true, then obviousness is no justification for our belief in its truth.

5.14 If a proposition follows from another, then the latter says more than the former, the former less than the latter.

5.141 If p follows from q and q from p then they are one and the same proposition.

5.142 A tautology follows from all propositions: it says nothing.

5.143 Contradiction is something shared by propositions, which no proposition has in common with another. Tautology is that which is shared by all propositions, which have nothing in common with one another.

Contradiction vanishes so to speak outside, tautology inside all propositions.

Contradiction is the external limit of the propositions, tautology their substanceless centre.

5.15 If Tr is the number of the truth-grounds of the proposition "r", Tr the number of those truth-grounds of the proposition "s" which are at the same time truth-grounds of "r", then we call the ratio Trs : Tr the measure of the probability which the proposition "r" gives to the proposition "s".

5.151 Suppose in a schema like that above in No. 5.101 Tr is the number of the "T"'s in the proposition r, Trs the number of those "T"'s in the proposition s, which stand in the same columns as "T"'s of the proposition r; then the proposition r gives to the proposition s the probability Trs : Tr.

5.1511 There is no special object peculiar to probability propositions.

5.152 Propositions which have no truth-arguments in common with one another we call independent.

Two elementary propositions give to one another the probability ½.

If p follows from q, the proposition q gives to the proposition p the probability 1. The certainty of logical conclusion is a limiting case of probability.

(Application to tautology and contradiction.)

5.153 A proposition is in itself neither probable nor improbable. An event occurs or does not occur, there is no middle course.

5.154 In an urn there are equal numbers of white and black balls (and no others). I draw one ball after another and put them back in the urn. Then I can determine by the experiment that the numbers of the black and white balls which are drawn approximate as the drawing continues.

So this is not a mathematical fact.

If then, I say, It is equally probable that I should draw a white and a black ball, this means, All the circumstances known to me (including the natural laws hypothetically assumed) give to the occurrence of the one event no more probability than to the occurrence of the other. That is they give — as can easily be understood from the above explanations — to each the probability ½.

What I can verify by the experiment is that the occurrence of the two events is independent of the circumstances with which I have no closer acquaintance.

5.155 The unit of the probability proposition is: The circumstances — with which I am not further acquainted — give to the occurrence of a definite event such and such a degree of probability.

5.156 Probability is a generalization. It involves a general description of a propositional form. Only in default of certainty do we need probability.

If we are not completely acquainted with a fact, but know something about its form.

(A proposition can, indeed, be an incomplete picture of a certain state of affairs, but it is always a complete picture.)

The probability proposition is, as it were, an extract from other propositions.

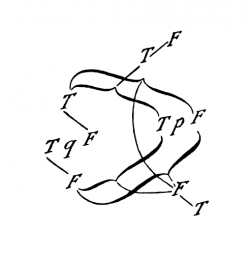

5.2 The structures of propositions stand to one another in internal relations.

5.21 We can bring out these internal relations in our manner of expression, by presenting a proposition as the result of an operation which produces it from other propositions (the bases of the operation).

5.22 The operation is the expression of a relation between the structures of its result and its bases.

5.23 The operation is that which must happen to a proposition in order to make another out of it.

5.231 And that will naturally depend on their formal properties, on the internal similarity of their forms.

5.232 The internal relation which orders a series is equivalent to the operation by which one term arises from another.

5.233 The first place in which an operation can occur is where a proposition arises from another in a logically significant way; i.e. where the logical construction of the proposition begins.

5.234 The truth-functions of elementary proposition, are results of operations which have the elementary propositions as bases. (I call these operations, truth-operations.)