Introduction to Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations

The LWP's Blog · Categories: Introductions, Philosophy

Introduction to Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations

By Filippo Villaggi, Désirée Weber, Michele Lavazza · 24 August 2025

The Philosophical Investigations, often cited alongside the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus as one of Wittgenstein's two masterpieces, is a complex, layered and fascinating work. This short introduction attempts to help the reader approach the work by providing a sketch of its main themes and by highlighting the innovative features of its style and method.

This blog post is part of a series of introductions to Ludwig Wittgenstein's individual published writings.

"Philosophical Investigations" is the title that Wittgenstein, starting from the mid-1930s, attributed to a collection of German-language manuscripts, often converted into typescripts, which he repeatedly, extensively, and compulsively revised in an attempt to shape his second book of philosophy.

Although the final version of the work was only composed between 1943 and 1945, with some marginal rehashes thereafter, it would be mistaken to think that the Investigations reflect a phase of Wittgenstein's thought whose scope is limited to the early 1940s. As he writes in the Preface, the ideas contained in the book are "the precipitate of philosophical investigations which have occupied me for the last sixteen years". Therefore, the Philosophical Investigations can be considered a synthesis of Wittgenstein's mature thought, following his return to academic philosophy in 1929. The result of so many years of gestation is a complex work, lacking a hierarchical structure and a definitive status like that of the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, but equally rich and surprising.

In the book's 693 numbered remarks, which follow slender and rarely explicit logical threads, Wittgenstein addresses many subjects, as summarized in the Preface: "the concepts of meaning, of understanding, of a proposition and sentence, of logic, the foundations of mathematics, states of consciousness, and other things". The author does not, however, provide a systematic treatment of them, but rather free remarks or, as he puts it, "a number of sketches of landscapes which were made in the course of those long and meandering journeys". This method corresponds to a renewed conception of the nature of the philosophical enterprise, which Wittgenstein presents in remarks 109–133: as he had already argued in the Tractatus, the aim is to solve philosophical pseudo-problems by dissolving the confusions that arise in the everyday use of language. However, for the author of the Investigations, this activity, this task of bringing clarity, no longer involves a refinement of the linguistic code according to ideal, logical criteria, as was the case in his earlier work. Instead, "Every sentence in our [ordinary] language is in order as it is" (§ 98): observations of this kind convey the idea that the principles that determine the meaningfulness of language reside within the use of language itself. And language’s intelligibility does not derive from compliance with absolute logical rules, but rather from "grammatical" use, that is, from the overall evaluation of the practical and diverse uses of signs. Consequently, the philosopher's task does not consist in discovering and articulating the logical foundations of language, but rather in offering descriptions of the myriad uses of language, thus elucidating those implications of the linguistic activity that are not immediately recognizable.

Thus, throughout the work Wittgenstein establishes some cornerstones of his new thought, such as the idea that "the meaning of a word is its use in the language" (§ 43): in order to know the meaning of a sign, one must observe the situations in which that sign is employed, examine the ways in which its usage is taught, and the customary practices by which that usage is transmitted, preserved, or transformed. Wittgenstein's constant appeal to imaginary scenes of instruction or plausible encounters with less complex languages aims to demonstrate, through an exploration of their most basic forms, how sophisticated linguistic-conceptual constructions (such as mathematics or abstract reasoning) are not based on unchanging logical laws, but on a set of elementary practices whose uses are mastered by the practitioners of a given language through training.

Wittgenstein’s text is a critique of classical theories of language because of its inclination to disappoint the rationalist perspectives with a contextual approach to language and to present many "language games" as "objects of comparison" (§ 130) for examining the meaning of expressions. This introduces a novel philosophical research method. He objects to the ideas of "representation", "proposition", and "logical atomism" as he had conceived them in the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus: language, according to the Wittgenstein of the Philosophical Investigations, only works when speakers are engaged in specific activities. With language, we do all sorts of things: that is why every use of language has sense within specific "forms of life", which are the set of contexts and circumstances that contribute to determining meanings. The famous expression "language-game" is precisely intended "to emphasize the fact that the speaking of language is part of an activity, or a form of life" (§ 23).

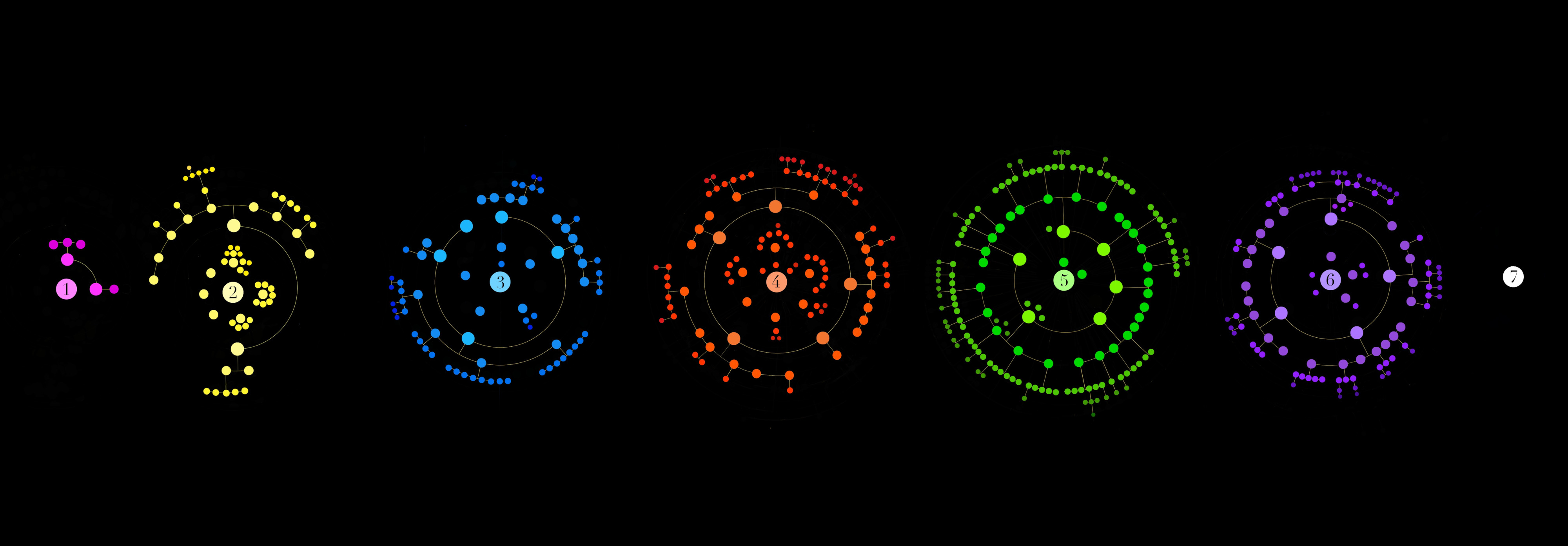

The themes explored by Wittgenstein in this work are too numerous and disparate to be briefly summarized. At the beginning of the text, he focuses on the ostensive learning of language, challenging ideas he attributes to Augustine. He discusses the concepts of "rule" and "understanding"; he introduces the notion of "family resemblances" (§ 67) to articulate a non-essentialist account of the similarities and differences in the use of signs in various contexts; he raises questions on the relationship between word and thought and the possibility of a "private language" in a series of famous explorations that include the example of the "beetle in the box" (from which the logo of our project is derived, § 293). Throughout, Wittgenstein unceasingly applies the methods of his new philosophical approach: by presenting several examples, thought experiments, imaginary situations, and comparisons, he examines the "misunderstandings concerning the use of words […] in different regions of our language". (§ 90) In doing so, he encourages the reader to adopt a more cautious and contextual approach to understanding language, ultimately showing that what we call "philosophical problems" are merely confusions, which are only dispelled by achieving a "perspicuous representation" (§ 122) of our ordinary language. Wittgenstein emphasizes philosophy as an activity, as opposed to a theory – and an activity that, if done well, may eliminate the need for it going forward.

The style of the Philosophical Investigations is often aphoristic and fragmented. Wittgenstein repeatedly expressed his dissatisfaction with the form he was able to give to the book – for example, at the end of the Preface, where he states: "I should have liked to produce a good book. This has not come about, but the time is past in which I could improve it". Wittgenstein’s iterative attempts to edit, arrange, and organize his ideas just so were extensive, but the book did not see the light of day during the author's lifetime. Even if one particular resulting typescript (Ts-227 in von Wright's catalogue) is considered to be among the most polished writings by the later Wittgenstein, it was only in 1953 that Wittgenstein's literary executors posthumously published the edited version of the text along with G.E.M. Anscombe’s English translation. The executors did so in a form that has not failed to provoke criticism due to the inclusion of a so-called "Part II" of the work. The content of this section consists of materials written between 1947 and 1949, which Wittgenstein made a selection of and had typed out (the resulting typescript was catalogued as Ts-234). Two of the literary executors, G.E.M. Anscombe and Rush Rhees, claimed that it was Wittgenstein’s intention to incorporate these contents into the final version of the work, but they also made it clear that it was their own decision to attach "Part II", in its relatively raw form, to the text of "Part I".

Additionally, the themes discussed in "Part II" are more closely related to the work Wittgenstein carried out on the philosophy of psychology after 1945. For these reasons, on our website, we exclusively reproduce what is known as "Part I" of the work, as do an increasing number of recent editions of the Philosophical Investigations – for example, Joachim Schulte's German edition. Schulte observes that the integration proposed by the literary executors, while it was welcome at the time of publication as it allowed the reader of the Investigations to become acquainted with additional hitherto unpublished reflections by Wittgenstein that would otherwise have remained unknown for many years, is now superfluous, because the content of "Part II" is now widely available, thanks, among other sources, to the electronic editions of the complete Nachlass.

It is not surprising that the Philosophical Investigations as a whole and many specific passages have generated lively interpretative debates and continue to do so. Its nature as an open work, the hypnotic structure of the argumentation, the innovative methodology, and the variety of themes make it a milestone in recent philosophy, as is proved by the massive influence this text has had on the development of ordinary language philosophy and on Western thought altogether in the second half of the 20th century and beyond.

About the authors

More from the LWP's blog

Happy 2026 from the Ludwig Wittgenstein Project!

Cover image: "Ludwig Wittgenstein Skjolden Norge 2024" by Vadim Chuprina, CC BY-SA 4.0